Reallocating and Rebalancing

Rethinking your investment mix is a critical part of smart investing.

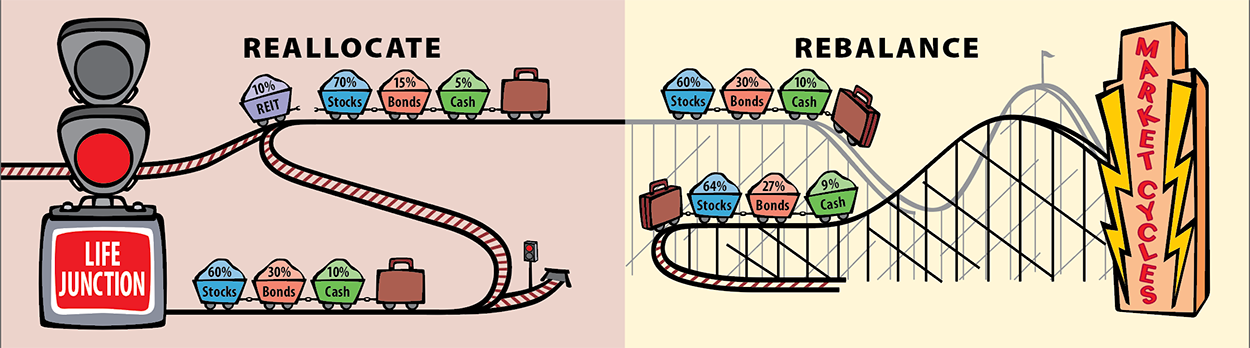

When you use an asset allocation strategy, you select a mix of investments to help you achieve your financial goals. Making this approach work for you requires your attention from time to time. For example, you may need to reallocate your assets to reflect changes in your goals, time frame, or the risks that concern you most. In addition, you’ll almost certainly have to rebalance your portfolio over time to keep it aligned with your allocation strategy.

THE RIGHT MIX

It can be easy to confuse reallocating and rebalancing. Both involve modifying the way your portfolio is spread across a variety of asset classes. And you make the modifications in similar ways, often by selling some investments and buying others. But the two serve quite different purposes.

When you reallocate, you alter the mix of asset classes in your portfolio to be more appropriate for your new investment focus. The change typically involves assigning different percentages of your account value to particular asset classes and sometimes adding new classes.

When you rebalance, you bring your portfolio back in line with the asset allocation you have chosen as an appropriate way to meet your goals. Without this readjustment, you could drift into an allocation mix that exposes you to greater investment risk, or one that is likely to provide a lower return, than you had anticipated.

KEEPING YOUR BALANCE

One approach to keeping your portfolio in line with your investment strategy is to rebalance your portfolio once a year as part of an annual financial assessment. Alternatively, you may want to rebalance only when your portfolio’s strongest asset class exceeds your target allocation by a specific percentage, say 10% or 15%. This approach reduces transaction costs and potential capital gains taxes.

You can rebalance your portfolio in a number of ways, similar to the ways you reallocate: selling off some holdings in the asset class that’s currently strongest or shifting new investments to the lagging class. Since the lagging class is likely to outperform in the next phase of the market cycle, you want to position yourself to take advantage of the opportunity to buy low now so you can sell high later.

LOOKING AT HIDDEN COSTS

If you have online access to your portfolio, you may be able to reallocate or rebalance as often as you wish. But there are a number of potential drawbacks to constant trading.

Most buying and selling comes with a price tag, which includes not only potential commissions or sales charges but also transaction costs. And, unless you’re trading in a tax-deferred account, you’ll owe capital gains taxes on any profits you realize. If you’ve owned an investment for less than a year before selling, those taxes are calculated at the same rate as on your ordinary income.

So there is a real risk that you may be spending more to make portfolio changes than you earn from making them.

A NEW PERSPECTIVE

By gradually increasing the proportion of insured and income-producing investments in your portfolio mix as your child gets ready to start college or you’re starting to think about retirement, you can help protect what you’ve accumulated and put new emphasis on owning assets that pay out regular interest or dividends.

You might want to begin reallocating by identifying some higher-risk, often more volatile, investments that have increased in value. By selling them and reinvesting the proceeds in a timely way, you can help protect against the risk of a major market downturn in the years just before you start withdrawing the money. You might also include asset classes you hadn’t focused on before, including real estate investment trusts (REITs) on the equity side and certificates of deposit (CDs) and US Treasury bills and notes in the cash category.

You can also modify your allocation by directing the new money you invest into income-producing or asset-preserving investments. This might allow you to hold on to some investments that have served you well over the years, and that you’d prefer not to sell, while still altering your asset mix.

A BALANCING ACT

One result of the normal ups and downs of the financial markets is that, at any given point, your actual portfolio allocation may be significantly different from the one you have chosen and would prefer to maintain.

This is because the various asset classes move through constantly recurring performance cycles. As a result, the return on equities is stronger in some periods and weaker in others. The same is true of debt and cash investments. And when one asset class is strong, the others often lag. This, in turn, affects the proportional weight of the asset classes within your portfolio.

As an example, consider a hypothetical $100,000 portfolio with 60% allocated to equities, 30% to long-term debt securities, and 10% to cash. If stocks, ETFs, and mutual funds provide a one-year total return that’s higher than the average historical rate while the return on fixed-income and cash investments is lower than average, the balance of the three asset classes in the portfolio shifts, perhaps to something closer to 64%-27%-9%.

While this shift isn’t particularly dramatic, another year or two of similar returns could increase the equity allocation to closer to 70% while reducing fixed income to 22% and cash to less than 8%. At this point, your portfolio is clearly more aggressive than you intended.